· by James Archer · 13 min read

What is Design Thinking?

There’s a common thread between companies like Tesla, Airbnb, Uber, SpaceX, Spotify, Square, Netflix and others that have successfully overturned decades of convention and built business empires around solutions that rendered their competitors almost instantly obsolete. It’s called “design thinking,…

There’s a common thread between companies like Tesla, Airbnb, Uber, SpaceX, Spotify, Square, Netflix and others that have successfully overturned decades of convention and built business empires around solutions that rendered their competitors almost instantly obsolete. It’s called “design thinking,” and while the name still unfortunately conjures an air of mysterious philosophy (or else of conceptual bull-crap), it’s actually a surprisingly practical and straightforward methodology for solving problems.

A definition of design thinking

Many intelligent people have defined design thinking in a variety of eloquent ways, each highlighting different various aspects of the methodology. I like to keep things simple, though. Here’s how I define design thinking:

Design thinking is an approach to problem solving that explicitly and methodically recreates the cognitive processes instinctively used by great designers.

Let’s break that down:

- “approach to problem solving”: Design thinking isn’t a design technique, nor is is limited to the design industry. Instead, it’s an approach to solving problems in general, and can be used in almost any industry, community, or situation.

- “explicitly and methodically”: The design thinking methodology doesn’t rely on any kind of elite instincts or rockstar talents. It’s all about the process. Complete novices can begin developing great ideas within minutes by just by following the basic design thinking phases and exercises.

- “recreates the cognitive processes”: The purpose of the design thinking methodology is to make conscious and intentional the kinds of things that more typically happened unconsciously and instinctively. By taking the magic out of people’s brains and putting it out on the table where everyone can see and touch it, design thinking turns inspiration and creative genius into a methodical and repeatable process.

- “great designers”: I’d love to live in a utopia where all designers thought like this, but the truth is that there are still plenty of pixel pushers, copycats, and paint-by-numbers designers out there. However, if you look at the best designers working, they’re probably following a mental process that’s very close to design thinking, whether they realize it or not.

While there are many other definitions out there that highlight different aspects of design thinking, I believe most practitioners would agree that this definition is a very sensible starting point. Additional resources:

- Behind the sticky notes: design thinking

- Design thinking as a strategy for innovation

- Design thinking…what is that?

Key principles of design thinking

Let’s talk a bit about the key principles design thinking principles that make it stand out from other methodologies:

- Empathetic It generates solutions based on an empathetic understanding of the people who’ll be affected, as well as the context in which those people find themselves.

- Methodical: It promotes a methodical approach to idea generation, rather than luck and inspiration.

- Holistic: It’s a big-picture methodology, focusing on the sweet spot where user goals, technical abilities, and business goals meet, rather than championing one at the expense of the others.

- Iterative: It encourages an cyclical prototyping methodology and continual improvement.

- Collaborative: It’s a participatory, team-based practice that seeks input from multiple sources. (It’s not about rockstars or gurus.)

- Optimistic: It’s based around fundamentally positive philosophy that assumes even seemingly impossible problems can be made better, and that even unusual ideas are worth considering.

If any of these six principles is missing from a design thinking process, there’s a good chance that the overall initiative will be in jeopardy. It takes all of them working together to really generate remarkable results. Additional resources:

A quick history of design thinking

The history of design thinking is somewhat convoluted, as is the case with most great ideas. Many of the core tenets of design thinking weren’t necessarily new, and had already been promoted at various times throughout history under a variety of names. For example, a movement called “cooperative design” evolved in Scandinavia in the 1960s and 1970s, and emphasized the importance of allowing computers users to collaborate directly with those who were producing software for them. In the United States, this movement came to be called “participatory design,” and is now often called “co-design.” That’s just one example of how the ideas behind design thinking can date back decades, or even centuries, depending on how deep you want to look. The ideas themselves aren’t new. They’re actually pretty timeless. However, the idea of design thinking has helped significantly in recent decades to unite those ideas into a coherent framework. In the 1980s and 1990s, scholars began to explore the cognitive aspects of design, analyzing it as a method for solving problems (rather than simply creating output). British design researcher Nigel Cross began to popularize the idea that design was a discipline that could stand on its own, separate from art, science, or engineering. He ruffled some feathers in the business and engineering worlds by suggesting that designers were not just important but actually central to the problem solving process. However, he also demystified what designers did by explaining that the design process—previous seen as an act of inspiration or genius—was actually a methodical and repeatable process. In the early 1990s, design theorist Richard Buchanan helped popularize the concept of design thinking as a robust problem solving methodology with his paper entitled Wicked Problems in Design Thinking, which is one of the first pieces that directly tied design thinking to the idea of innovation across disciplines. (The phrase “wicked problems” wasn’t just an attempt to spice up the title of an academic paper, but rather a term used since the 1960s to describe problems that are difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, evolving, or contradictory requirements. It was often used to describe public policy issues like climate change, drug trafficking, or nuclear weapons.) Today, design thinking is widely accepted as a powerful methodology for generating new ideas in solutions across countless disciplines. Manufacturers use it to develop new products and features. Software companies use it to identify new opportunities to appeal to users. Non-profits use it to find more efficient and effective solutions that further their causes. Educators use it to find new ways to help people learn in increasingly complicated and resource-constrained situations. Everyone’s using design thinking. Additional resources:

- A brief history of design thinking

- Design thinking - history

- Design thinking: get a quick overview of the history

The design thinking process

While the exact description of the design thinking process may vary depending on whom you ask, the overall principles have remained roughly the same since the beginning. And while it may seem abstract on first glance, it’s actually a powerful framework for generating truly innovative ways to solve real-world problems.

Design thinking phases

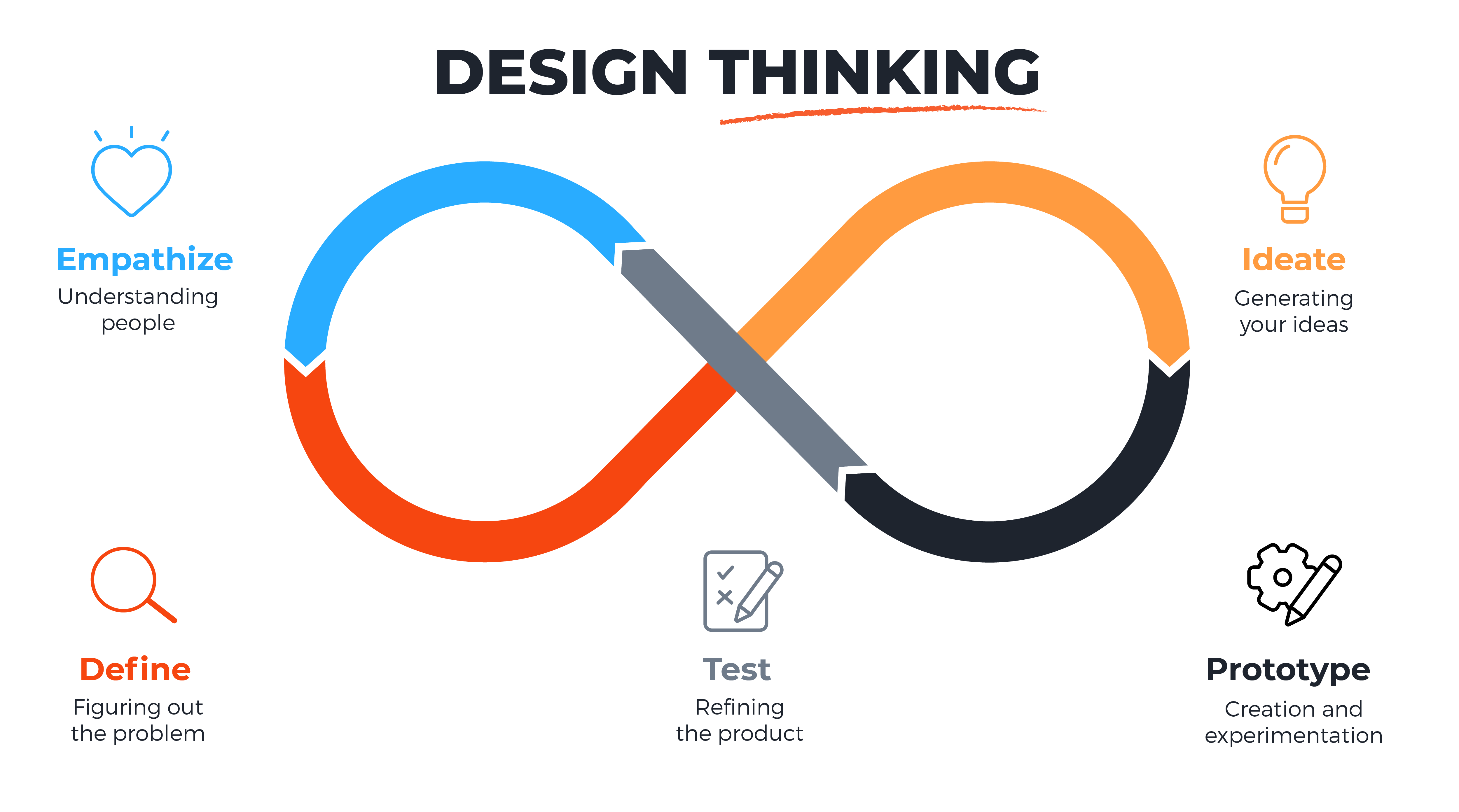

The Stanford d.School’s design thinking methodology, perhaps one of the best known, describes five phases of design thinking as follows:

- Empathize: understand the human side of the problem

- Define: bring clarity and focus to the problem

- Ideate: develop new ideas and potential solutions to consider

- Prototype: quickly turn theory into action with rough-but-usable examples

- Test: gather real feedback on prototypes from users

There have been various other design thinking phases proposed as part of an overall design thinking process, but in reality they all tend to be restatements of the same basic process using slightly different words or divisions between the stages. However, the battle-tested Stanford model is probably as close as we’ll get to a generally-accepted model of design thinking phases, so I tend to use it as the de facto standard. Additional resources:

Iterative design

A step that’s sometimes under-emphasized in the Stanford model is the idea of iteration: going back to the beginning of the process and repeating it again. In most cases, a single journey through the design thinking process (Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test) isn’t enough to provide a refined solution to a complicated problem. After all, once you’ve reached the Test stage, you have to do something with the test results, right? The logical next step would be to Empathize with the users based on those results, and so the design thinking phases begin again.

The design thinking process is fundamentally cyclical. The greatest products ever designed weren’t just designed once, but instead went through progressive cycles to get better and better based on continued testing and user input. The original iPhone, for example, was a design marvel for its time. However, if you actually go back and use a first generation iPhone, it would seem barbaric compared to its heavily-refined contemporary equivalent. From a UX perspective, you can think of each of the design thinking phases as leading toward a slightly more refined prototype. The first prototype of a mobile app, for example, might simply be a brief that describes the app at a high level. After testing that brief and receiving feedback on it, you might put together a set of functional specifications as a second prototype. Then maybe a high-level navigational structure. Then wireframe diagrams. Then mockups. Then an interactive prototype. You keep looping through the design thinking process until you achieve a launch-worthy product, but even then the job isn’t done. Once the product is out there on the market, you immediately go back to testing and empathizing, and start the design thinking process all over again for the next version. Good design is almost always iterative design, and it’s fundamental to the design thinking process. Don’t think of those design thinking phases as being something you go through once over the course of a project, but instead as something you might loop through several or even dozens of times. Additional resources:

- Mastering design thinking and the iteration process

- Iterative design

- Three reasons to design iteratively

Why design thinking?

The five design thinking phases (Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test) may not seem particularly remarkable at first, but diligently and methodically following that process will generate innovative and effective results with remarkable consistency. It’s essentially a formalization of the process instinctively used by some of the world’s most innovative and creative people, taking out of the realm of “inspiration” and “genius” and making it accessible and usable by essentially everyone. Even designers themselves tend to perform significantly better when they consciously follow the design thinking process instead of leaving it up to their instincts and reflexes. This way of approaching problem solving contrasts sharply with a more common or traditional method of thinking, which I sometimes call “management thinking” because it’s so common in corporate work environments.

Design thinking

Management thinking

Work to genuinely understand the user/customer

Assume you already understand the user or customer

Build clearly-defined models of the user, the problem, etc.

Assume everyone’s in agreement about how users think or behave

Generate new and possibly never-attempted solutions to your problems.

Choose from among common, accepted solutions to your problems.

Prototype the solution in multiple iterations (Agile)

Build the solution in a single straight shot (Waterfall)

Actively test your solution to find additional ways to improve it

Save time and money by fixing only the most urgent functional bugs

The management thinking approach is certainly understandable, given the realities of corporate life. A typical businessperson, faced with the pressures of fixed deadlines, thin budgets, tightly-defined contracts, and an institutionalized fear of uncertainty will certainly tend toward making short-term decisions that are completely contrary to the design thinking process. However, the consequence of doing so plays out in the long-term, when the solutions fail to remain competitive in the market, customer satisfaction continues to decline, and poor decisions wind up taking months or years to fix. While it may feel a little open-ended at first, the design thinking process actually often winds up being the very fastest route to a remarkably high-quality solution. There’s a reason that many of the world’s most successful companies have adopted design thinking as a key part of their cultures, where many colossal business failures have associated with traditional management thinking. Additional resources:

- Why design thinking should be at the core of your business strategy development

- The five big benefits of design thinking

- Design thinking comes of age

Design thinking and innovation

The design thinking methodology is perhaps best known for its ability to consistently generate ideas—and not just new ideas, but also good ideas. Solving problems with design thinking goes beyond mere brainstorming because it’s rooted in empathy for the end user, which means it’s not just about coming up with random ideas that might work and seeing which ones stick, but it actually involves methodically generating new ideas based on existing constraints, as well as questioning those whether those constraints are necessary in the first place.

Q: How many designers does it take to put in a lightbulb? A: Why a lightbulb?

Traditional thinking is focused primarily on narrowing down multiple options to identify which of them is the best one. For example, if you start with options A, B, and C, you might do a cost/benefit analysis and determine that option B will provide the most value relative to its cost. This is sometimes called “convergent thinking,” because its goal is to converge from multiple options to a single option. Design thinking includes convergent thinking, but not as a first step. Before it, there’s something called “divergent thinking,” which is focused on generating new options to consider, based on the question at hand. If you go back and look at your problem again, you may discover that you have options D, and E, and even R and 7. You then wind up with options completely different than those you started with, and at least a few of them might prove to deliver significantly better results. For example, a traditional approach to the question “How should I get an education?” might center on finding the right university for the career you’re hoping to pursue. A design thinking approach to the same question, however, would first ask questions like “How might I get an education besides university?” “How else might I learn the same skills more efficiently?” or “How might I find similar work without requiring a formal university education?” Many of the options generated by that divergent thinking process may not survive the convergent thinking process that follows it, and that’s okay. However, by giving yourself additional options to consider, you introduce the possibility for a remarkably different solution. In the example we just talked about, it might work out that performing an apprenticeship under an experienced industry expert and then going into business for yourself winds up making more sense than taking on a crushing student loan debt. That’s an option you never would have come up with if you were only focused on deciding which university to attend. This is what separates design thinking from so many other methodologies. It’s a consistently-reliable process that allows you to generate ideas that are both new and effective, giving you options you never realized you even had.